|

|

|

|

| Index

to stuff commented on |

BRIEF

REVIEWS:

1

|

|

Zombie

Holocaust

Goke,

Bodysnatcher from Hell

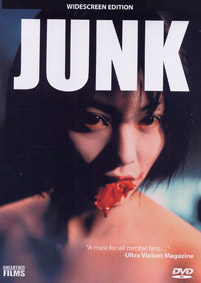

Junk

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

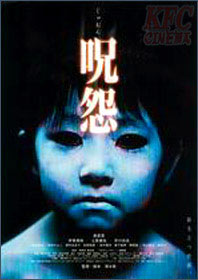

Ju-On: The Curse / Ju-On: the

Curse 2

Bubba Ho-tep

Virus

Ju-On: The Grudge

The Ape Man

Revolt

of the Zombies

Ghost Ship (1952)

The Entity

13 Gantry Row

The Changeling

Exorcist:

The Beginning

The Invisible Ghost

The Story of Ricky

13 Ghosts (1960)

|

House of the Dead

Shock Waves

They Came Back (Les Revenants)

Zombie Honeymoon

Dracula 3000

The Uncanny

Premonition (Yogen)

Dead Birds

Possessed

Gargoyles

FeardotCom

The Asphyx

Haunted (1995)

The Darkling

Tormented

Lisa and the Devil

The Black Cat

Cursed (Japanese)

More reviews |

|

|

Cursed [aka 'Chô' kowai hanashi A: yami no karasu] (Japanese, 2004) -- dir. Yoshihiro Hoshino

Welcome to the Mitsuya Mart!

Re-titled Cursed for international release, this J-Horror entry is so deliciously bizarre, idiosyncratic and creepily humorous, it makes an effective addition to the already odd Asian ghost-story sub-genre. While no upper echelon spook classic, the film works in its own terms, despite rough patches.

For a start it looks pretty good. Though low budget and filmed on digital video, it doesn’t significantly suffer from these drawbacks – not unless you are irrevocably wedded to slick Hollywood production values. If you aren’t, you might find that its video origins give the film’s interior shots (in particular) a sort of starkly lit garishness that accentuates the sense of exposure and threat pervading events. Though its oddball combination of bizarre humour and horror can seem somewhat jaggedly melded together at times, the result has a definite manic attraction all its own. Its unsettlingly alien qualities add to the overall effect.

Cursed is set in and around an inner-city suburban convenience store, the Mitsuya Mart. This is a less-than-convenient convenience store, in that the owners are certifiably mad, and the Mart’s ambiance and reputation are such that local residents never shop there. Only those from out-of-town, or those who haven’t been paying attention, risk popping in to pick up some emergency supplies. To do so is to court death. If your purchases add up to 666 yen or 999 yen or even 699 yen, it is likely that you’ll be tracked to your apartment by a huge sledgehammer-wielding maniac, attacked psychically and emotionally while bathing or preparing dinner, haunted by a parker-wearing phantom, hit by a bus, or otherwise visited by spectral, and dangerous, scraps of weird-shit metaphysical spookiness. So if your purchases fortuitously add up to 820 yen, resist the temptation to buy a counter treat as you stand ready before the cash register, or else you’ll find that the total will hit 999 after all – and then you’re done for.

The loose, anecdotal visitations that make up much of the film were apparently taken from a book series popular in Japan. As such, Cursed relates to what is becoming a popular Asian sub-sub-genre – the ghost movie based around a series of anecdotal scare moments. Ju-on: Grudge fits into this mould, though the Pang Bros’ Eye 10 and Tales of Terror from Tokyo and All Over Japan offer more direct examples: films of an anthology nature, with sometimes tenuous (or non-existent) arcing linkages. This anecdotal approach can work rather effectively for ghost stories, as that is essentially what they are, even when given a more directly plot-structured framework; the approach harks back to the ghost story’s origin – the "Did you hear about…?" mode of "campfire" folktale – and gains a sort of resonance from that association.

Meanwhile, and most importantly, the stark atmosphere is insidiously unnerving, the moments of haunting satisfyingly creepy, the acting good, and the framing moments strong. Young newcomer Hiroko Sato, as the resiliently cheerful part-time check-out chick, manages to drag viewer sympathies into the story and to provide an anchor for identification. Not any easy task. Though the film does provide some "explanation" for the spooky occurrences, it in no way connects the dots in regards to the exact nature of individual events – because, essentially, they represent disparate hauntings brought together conceptually under the wide embrace of the cursed Mart. As in much Japanese horror, "explanation" is not the point – "Don’t look for meaning," one character advises. "There is none." But the film needed a focus, and Ms Sato provides it.

The Japanese title translates as something along the lines of "The Most Horrible Story 'A': Crows of Darkness", which in itself encapsulates much about the film’s tone. "Crows of Darkness" would have been a much better title for the US release. This would have avoided the tendency for the film to be confused with the higher profile werewolf movie Cursed directed by Wes Craven, which was released about the same time – and sounds much less boringly generic.

18 December 2005

Return to top

|

This

section is designed as a place where I can add quick comment,

short reviews, random thoughts and observations on films

and TV related stuff, as well as books perhaps ... on

an ongoing basis. You'll probably note a certain lack

of objective restraint at times. Sorry. |

The Black Cat (US, 1934) -- dir. Edgar G. Ulmer

Featuring stellar and subtly nuanced performances by Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi, The Black Cat is a stylish, marvellously effective horror film that creates a dark, oppressive metaphor for the corrupting influence of past iniquities. Ulmer was a fascinating director -- never feted within Hollywood and mainly confined to low-budget genre flicks, he nevertheless managed to produce this classic of horror, Detour (one of the great film noirs) and a slew of flawed but intriguing cheapies, such as The Amazing Transparent Man and Beyond the Time Barrier, made back-to-back in 1960 over a two-week period. In The Black Cat, he creates such an atmosphere of claustrophobic intensity and perverse evil that the film managed to get itself banned in various regions, despite the fact that the violence generally remains off screen and implication rules. The film contains a wealth of perversities: hints of necrophilia, references to mass slaughter (Poelzig's house is built of the site of a wartime massacre), a flaying, the corpses of ex-wives suspended in death in a basement "museum", murder, Satanism, and an air of obsessive and simmering revenge. What's more, inspired as it was by the real-life "black magician" Aleistair Crowley, its credentials would not have gone down well in polite society. Then there's the wonderfully "modernist" set design and the strange appearance of Karloff's world-weary devil-worshipper, Hjalmar Poelzig. Even his vengeful enemy, Dr Vitus Werdegast (Lugosi), with his "morbid fear of cats", supplies little by way of heroic virtue, seeming to be motivated by a death wish as strong as Poelzig's. Death is everywhere in fact, offering more than a hint of post-war malaise. It is a moral death that afflicts them both; they are undead ghosts playing out the final act of a long-running emotional conflict. Says Poelzig to Werdegast: "Are we not both the living dead? And now you come playing at being an avenging angel, childishly thirsting for my blood. We shall play a little game, Vitus. A game of death..." What this all adds up to is a treat for horror fans that is comparable to nothing else in the history of the genre.

22 November 2005

Return to top

|

|

Lisa

and the Devil (Italy, 1973) [aka Lisa e il

diavolo] -- dir. Mario

Bava

Lisa

and the Devil is a film that has been much

abused. At the time of its first release, The

Exorcist was making a killing at the box-office,

so of course a surreal and lyrical film with "Devil"

in the title wasn't going to make it to the screen without

studio interference. In this case the interference was

considerable. Bava's morbidly beautiful masterwork was

totally re-edited, new footage of now "standard"

demonic possession was added, and it was re-named The

House of Exorcism. Bye-bye lyricism. Bye-bye

artistic integrity.

The

original film is arguably a career high from a man who

made a number of horror masterpieces. It contains no

demonic possession, no head-spinning, no echo-chambered

bass voices, no levitation, no green-pea spewing, no

"Don't break my balls, priest!" retorts. Lisa

and the Devil does not, in fact, concern itself

with demons or exorcisms at all; it is a poetic ghost

story, where Telly Savalas' humorous butler/devil is

a claimer of the dead, a sort of grim reaper, apparently

causing past events to replay in order to ensnare the

living. Visiting tourist Lisa (Elke Sommers) is part

of a bus tour examining an ancient fresco in an Italian

town square; she becomes fascinated by an image depicting

the Devil carrying off the souls of the dead, but is

enticed out of the bustling square by music, which,

it turns out, is produced by a music box complete with

revolving dolls -- the most prominent of which is a

skeletal Death figure. The dance-of-death box is owned

by a strange man who looks a lot like the Devil depicted

in the fresco. Lisa flees, but suddenly the town is

deserted and she is lost -- and eventually ends up taking

refuge in a lavish mansion where the inhabitants play

out an elaborate history of love, betrayal and death,

engaging in their own dance of death. Lisa is the spitting

image of Elena, who was at the centre of the passions

being re-enacted. Soon there is violent death and terror...

and all are lost in events that have clearly already

happened and are now happening again -- or are still

happening.

The

film contains many scenes of visual poetry; one that

is particularly memorable depicts the son of the household

having sex with Lisa, who is drugged and comatose, in

a bed that contains the decayed corpse of Elena and

is surrounded by obscuring gauze, mouldy cake and rampant

vegetation. Implications of necrophilia and incest abound,

and bloody murder splashes gouts of red across the film's

lush colour scheme. Confusion between large doll-figures

(carted around by the devilish butler) and their human

counterparts, an atmosphere of increasing decay, and

images of vast and shadowy emptiness give the whole

thing an air of temporal confusion that is thoroughly

unique.

21

November 2005

Return

to top

|

|

Tormented

(US, 1960) -- dir. Bert

I. Gordon

Films

are a product, and a victim, of their time and circumstances,

some more markedly than others. But this doesn't mean

they can't be enjoyed and appreciated. Tormented

is a noirish ghost flick by exploitation cheapie director

Bert I. Gordon, who is better known for his movies about

big things -- his best probably being The Amazing

Colossal Man. The thing about Gordon is this: he

didn't have much money, had a limited technical repetoire,

and was prone to doing the obvious, directorially. But

his films often have aspirations to better things and

show hints of what those better things might be.

Tormented

is a good example. It is a small film that makes the

best of a beach/island/lighthouse setting, in which

environment a supernatural love-cum-revenge tale plays

out to reasonably good effect, all things considered.

Richard Carlson stars as jazz pianist Tom Stewart, who

is visited on the eve of his wedding by his lounge-singer

ex-lover with threats of exposure. "No one will

have you except me," she threatens. When she accidentally

falls off a derelict lighthouse, he deliberately avoids

saving her, but is subsequently riddled by guilt. Is

it simply guilt that evokes a subjective ghostly presence? Well,

not entirely. Others do smell her perfume, and objects (such

as a wedding ring) disappear, a recording of the ex

singing "Tormented" refuses to be silenced,

her footprints appear in the sand. Yet there remains

an ambiguity about the whole thing that allows us to

experience the haunting as a metaphor for Stewart's

emotional state without feeling as though we are being

manipulated too much.

Some

of the scenes and effects are hokey, no doubt about

that. Some things would be better half-seen -- the singer's

disembodied head, for example, is hard to take seriously;

and her footprints actually appearing alongside those

of Stewart and his fiancé as they walk along

the beach would have worked better as a static manifestation -- being there when he looks but not actually appearing.

But other scenes carry considerable impact: the first

appearance of the ghost as a diaphanous windblown figure

hovering in the air outside the lighthouse railings;

the singer's body rescued from the sea and becoming

seaweed in Stewart's arms; flowers and bouquets wilting

as an invisible presence makes its way down the aisle

in response to the minister's ritual appeal for those who "object"

to the marriage to speak up. The ending is both grim and effective.

Driven to murder by the need to cover up his guilt (or

by the taunting of the ghost), and even contemplating

killing the young sister of his bride (because she witnessed

the deed), Stewart falls to his death thanks to the same faulty railing

that brought about his ex-lover's earlier demise and a sudden

"in-your-face" appearance of the ghost. On

a benighted beach, watched by the wedding crowd, divers

drag a body out of the sea -- but it is the ex-lover's.

They then drag out Stewart's corpse; as they dump him

on the sand next to the ex-lover, her arm falls across

him in a possessive embrace -- and she is seen to be

wearing the missing wedding ring.

Yes,

the film does show its age, its time (especially

in some of the rather strained "hip" dialogue) and its budgetary limitations,

but it is an entertaining B-film anyway and resonates with the

power of an effectively, if a bit shakily, realised

metaphor.

18

November 2005

Return

to top

|

The

Darkling (US, 2000) -- dir. Po-Chih

Leong

This

is another example of low-budget TV filmmaking that, to

my mind at least, thoroughly justifies the medium as offering

opportunities for small and quirky projects. Of necessity

eschewing spectacle and complex SFX, The Darkling

proves to be an intimate, intelligent parable exploring desperation,

the desire for "wealth, happiness and fame"

and the associations we are willing to make in order to

achieve our ends. Using the always fascinating world of

the collector as a central metaphor, the film successfully

creates its own dark atmosphere and generates enough suspense,

albeit low-level, to keep any willing viewer involved.

The fallen, djinn-like cherub that is the Darkling is

a shadowy, ambiguous and creepy creation, effectively

encapsulating the darker possibilities of the film's world;

its depiction here is effective if limited by the production's

low budget -- but it works nevertheless. The actors are

serviceable to good, with F. Murray Abraham as a stand-out,

though Aidan Gillen does a fine, low-key job in the role

of the main protagonist. With a carefully constructed

script, good direction and an earnest technical sincerity,

The Darkling is the sort of low-budget film that

would not get made if the cinema box-office were the only

criteria governing such things. The film was never one

that was going to be welcomed, enjoyed or even tolerated

by everyone, and nor was it going to be of great significance

within the genre. But it has an integrity of its own and I

for one am glad it had a chance to be made. (The other

benefit for the film collector, of course, is that, being

utterly insignificant in terms of industry profile, the

film was released to DVD very cheaply, despite an excellent

transfer and good general presentation.)

18

November 2005

Return

to top

|

Haunted

(UK/US, 1995) -- dir. Lewis Gilbert

The effectiveness of this ghost movie based on the novel

Haunted by James Herbert derives in part from the

fact that it draws on a pre-eminent literary tradition

(specifically that of the English ghost tale, full of

class-conscious social politics and a strong sense of

history), while maintaining a modern sensibility. With

its period setting, and in particular the iconic aristocratic

personalities inhabiting Edbrook, an imposing English

manor house, it combines Old Dark (and Haunted) House

imagery with effective dramatics to draw us in and keep

us on the back foot right until its turnabout ending.

The Mariell siblings are played effectively by Kate Beckinsale,

Anthony Andrews and Alex Lowe, and represent a classically

eccentric bunch -- upper-class, ostentatiously "clever",

self-indulgent and thoroughly spoiled, so much so that

an unhealthy and insidious undercurrent becomes apparent

right from their introduction. Aidan Quinn's troubled,

but sceptical, academic, Prof. David Ash -- invited to

Edbrook in order to dispel nanny Anna Massey's fear of

the ghost(s) that supposedly haunt the place -- brings an

appropriate mix of knowing objectivity and vulnerability

to the scenario, harbouring as he does much lingering

guilt over the childhood death of his sister. This, of

course, allows for the introduction of the sort of ambiguity

that works so well in ghost stories: Are unnatural occurrences

at the house a function of his own unresolved emotional

traumas, garnished with a fair measure of sexual confusion

generated by Christina Mariell (whose naked indifference

to social conventions seems both stimulating and sinister)?

Or is there more to it? Of course there is more to it,

and the viewer knows this, but the ambiguity effectively

moderates our responses and, given a bit of artistic suspension,

encourages us to become absorbed by the possibilities.

That this 1995 supernatural drama plays a similar endgame

to the 2001 film The Others should not surprise

us; that particular trope has been around for some time.

However, it's a measure of this film's success - and the

success of The Others for that matter - that we

allow ourselves to be pleasantly surprised at the end,

instead of ignorantly dismissing it as derivative.

18

November 2005

Return

to top

|

| The

Asphyx (UK/US, 1973) -- dir. Peter Newbrook

Made

by new company Glendale at a time when the Hammer crew

were resorting to increased levels of sex and violence

to combat escalating box-office competition, The

Asphyx seems staid and traditional, despite

its intriguing premise. Though based on an interesting

scenario, the film exhibits lazy writing and a reluctance

to develop the implications of its concept through to

some logical conclusion. The 2.33:1 aspect ratio and

shadowy visuals suggest an opulence of imagination that

doesn't transfer over to the story itself, and one can't

help coming away from the film with a feeling that its

main character -- an aristocratic scientist obsessed

with death and thwarting its hold over humanity -- would

have been better depicted by someone with the experience

and horror-film savvy of contemporary Peter Cushing.

Cushing's performance would have suggested greater complexity

and conviction, and would have brought an appropriate

manic poignancy to the role. Robert Stephens is servicable

enough, but he never quite manages to make his character's

motivations totally convincing. And his ornate contrivances

to place himself, his daughter and her fiance near to

death seem based more on a desire for dramatic spectacle

than on the need to come up with a logical, and safe,

mechanism derived from necessity.

With

its framing device (albeit ill-used), its period setting,

its original scenario and effective cinematography,

the film does go some way toward forging its elements

into a dark parable of grief and obsession (and it is

certainly creepy in those moments when the Asphyx --

the spirit of death -- manifests in Cunningham's light

and shrieks in protest at its entrapment). But in the

end it falls short in many areas, most notably failing

to give credibility to its incredible events. Ultimately,

there are too many contrived actions and undeveloped

implications for the film to succeed in coalescing into

a dramatic whole.

16

November 2005

Return

to top

|

| FeardotCom

(UK/Germany/Luxembourg/US, 2002) -- dir. William Malone

The

basic critical response to this horror film, from professionals

and general public alike, is fairly consistent: they

all hate it. I only discovered this after I watched

it and then looked around for some intelligent critical

discussion. But there wasn't much of that out there

-- just sarcastic dismissal, often at considerable length.

Some reviews do attempt to explain why it is so bad,

mostly by referring to it as being (a) derivative of

Ringu and its US remake, and (b) narratively

inept and incoherent. Personally, however, I had seen it

as taking a slightly different approach to themes made

popular by The Ring, and had no trouble "understanding"

what was going on in the film. So the fact that so many

saw it as intolerably derivative and "making no

sense whatsoever" came as a surprise. Even Roger

Ebert, who takes a tolerant approach to the film --

one determined by his appreciation of its excellent

visual stylings -- considers the plot to be incoherent.

Others simply have contempt and disdain for it as "bad

filmmaking": bad acting, bad dialogue, bad direction.

Loathing is almost universal.

Without

a doubt the film avoids spelling out its narrative semantics

in so many words. Nor is the plot transparently obvious.

But I would contend that the through-line is there and

that as a whole the story hangs together. Occurrences

within the film can be explained and it seems

resistent to logical querying only to the extent that

most ghost films remain a few steps beyond the rational.

That it suggests Ringu is certain; that it

was deliberately trying to steal from that film is less

certain. The director has apparently claimed that he

hadn't seen Ringu (or The Ring) when

he made it. Even if he's being deliberately forgetful, those elements that

suggest Ringu have quite a wide-ranging currency

and the basic thrust of the film takes it to different

imaginative places anyway. The mix even seemed rather

original to me. Moreover, I thought the acting was OK,

if not inspired (in particular, the romantic chemistry between the

two leads is all but non-existent), the script was

fine (if a little obtuse at times and a little messy

at others), and the direction was inventive. The film

is not perfect, but does display technical competence

and in the end offers decent entertainment value.

Here's

my take on the story. The Doctor (Stephen Rea) is a

psycho bent on acting out his obsession with mortality,

killing his victims online via webcam according to his

own rules and as a comment on humanity's essentially

voyeuristic fascination with death and suffering. One

victim -- the Doctor's "favourite" -- returns

as a ghost, but tied to the internet, through which

her suffering had been broadcast; now she is bent on

revenge. A website that offers images of her suffering

is the means by which she can manifest, the fears of

those who go there and buy into the morality of such

a site giving her the psychic means to gain entry into

the world. Why does she appear to victims as a child?

Perhaps because it is to memories of herself as a child

that she is most connected. At any rate, the bizarre

killings (which reflect the victims' deepest fears and

must therefore be seen as subjective in nature) lead

to investigation by a policeman (Stephen Dorff) and

a health inspector (Natascha McElhone), and thus, eventually,

guide these two protagonists to the Doctor's current

lair. It is important to note that the deadly feardotcom

website is not the same as the Doctor's website, the

URL of which is changed after each killing. Where did

the feardotcom site come from? Who knows? As a distillation

of the ghost girl's suffering, presumably she created

it herself, supernaturally. Why does she take it out

on innocent viewers? Well, that's what vengeful ghosts

do, and in this case she only attacks those who enter

the site knowing it is about torture and death. As such,

they are not innocent at all, on one level. At the climax,

Detective Reilly, dying from the Doctor's attack, brings

the feardotcom site up on the Doctor's screens precisely

in order to allow the ghost girl to manifest and gain

her ultimate revenge -- on the one who was responsible

for her death. She does so in an appropriate manner.

Sure,

there are still unanswered questions, though not at

the level of the main storyline. So why do so many viewers

fail to appreciate what went on? Who knows? Certainly

the film suggests Japanese horror such as Ringu

in its refusal to fully rationalise its ghostly goings-on

-- but it does create its own "rules" and

pretty much sticks to them. It also offers a fairly

intricate narrative structure, with lots of interweaving

of incidents and images without verbal backup to carry

the meaning. Perhaps it does these things to an extent

unjustified by its emotional content and hence makes

unreasonable demands on the viewer's tolerance. Perhaps

its characters simply aren't strong enough to make the

average viewer willing to struggle with its cinematic

obscurities; in other words, it doesn't foster suspension

of disbelief. Many viewers are simply bored. For whatever

reason most seem more inclined to nitpick than to surrender

to the film's story, pointing up supposed inconsistencies

and illogical behaviour that, in other flicks, would

simply be ignored. That, too, is a failing, I guess.

Still,

I think it has value as a ghost film, paddling in the

waters springing from Ringu's well and offering

a variant take on its themes.

16

November 2005

Return

to top

|

|

Gargoyles

(US, 1972) -- dir. Bill L. Norton

Rubbersuit

monsters aren't confined to Japanese daikaiju eiga

[giant monster films]. This early '70s made-for-TV monster

flick sports a host of them, with makeup courtesy of

soon-to-be-SFX-superstar Stan Winston (who would get

involved in John Carpenter's makeup extravaganza The

Thing in 1982 and would subsequently be responsible

for creature effects in 1987's Predator).

The gargoyles are varied in form, well-constructed,

and both sinister and cute; moreover, they show themselves

rather good at destroying buildings with their bare

claws, lurking among rocks and desert scrub, and leaping

on passing riders. Though the suits suffer from "knee-wrinkle"

and in a couple of shots the zipper is visible, the

designs are so effective I'm inclined to be forgiving.

After all, such things are traditional. What matters

is that the film transcends its low-budget made-for-TV

origins, managing to be entertaining and, at times,

creepy.

For

what it is, then, Gargoyles is a enjoyable

film, with enough that is memorable to give it staying

power. Yes, it looks like a TV movie, being unable to

open out as widely, plot-wise, as it should, lacking

the right level of gore, and veering away from sexual

undercurrents that are there but unduly muted. There

is something about the pacing of dialogue scenes that

says "telly drama", too. But director Norton

does particularly well during certain key scenes (the

early attack on the hero's car, the destruction of Uncle

Willie's shed, the siege of the motel room) and the

actors are mostly good -- from Cornel Wilde as the briefly

sceptical popular anthropologist, Jennifer Salt as his

revealing-halter-top-clad daughter, Grayson Hall as

the perpetually tippling landlady, Scott Glenn as dirtbike

rider-turned-good-samaritan (in the manner of Steve

McQueen in The Blob), and Bernie Casey

as the deep-voiced lead gargoyle, evoking both Tim Curry's

Satan in Legend and the Creeper from

the recent Jeepers Creepers. I particularly

enjoyed Woody Cambliss' Uncle Willie, the roadside weird-shit

man. They all worked effectively, even when the dialogue

became a bit loose and the dramatic pace faltered.

The

settings, too, are a positive asset. Filmed in the Carlsbad

caverns and New Mexico, the splendid rock formations

and contrasting desert openness give the film real class.

What is lacking is a bit of arcane stylishness in lighting

and general approach. The cathedral-like rock formations

offered the director a wonderful opportunity to evoke

the sort of gothic grandeur we associate with traditional

stone gargoyles. Over all, the film's gargoyles are

too well lit -- and too often we see them upright, simply

standing or running around. I kept imagining the camera

catching them on the top of cliffs, leaning from ledges,

hunched and looming over the human characters the way

gargoyle statuary looms over visitors to Notre Dame

cathedral and similar religious edifices. We should

have been given glimpses of them swathed in shadows,

barely animate, like ill-lit, benighted statues come

to ambiguous life. But it didn't happen. Despite the

good bits, this stylistic lack of imagination made the

film seem undercooked. It is undoubtedly an enjoyable

cult monster flick, but it could have been a classic.

In

this current frenzy of remakes, usually of classics

that don't need to be remade, Gargoyles

represents just the kind of flick that would be a natural.

Some atmospheric CGI gargoyles would go down very well,

despite the appeal of the original costumes.

20

October 2005

Return

to top

|

|

Possessed

(US, 2000) -- dir. Steven E. de Souza

In

the late 1970s, demonic possession films became a standard

of the horror genre after the extraordinary box-office

success of Friedkin's The Exorcist.

Most of the direct rip-offs were, of course, only lukewarm

regurgitations of that film -- and where filmmakers

deviated from the formula, the result tended to be audience

disinterest and critical scorn. Boorman's Exorcist

2: The Heretic, for example, is undoubtedly

a flawed film, but not the disaster most critics make

out. What it is is wildly idiosyncratic and divergent

in approach and thematics, and this rather bemused and

disappointed punters.

The

urge to replicate The Exorcist faded

somewhat as the years went by, though comparable demon

flicks continued to be made, and the influence of the

patriarchal granddaddy of possession films lingers.

Possessed, made in 2000 for TV, does

not try to remake The Exorcist as such,

but there are, inevitably, similarities. Supposedly

based on the same "real-life" incident that

inspired The Exorcist, the film sticks

more closely to that historical event than its predecessor

did. Hence, it is set in the late 1940s-early 1950s,

offering an effective period feel through both set design

and character attitudes; moreover, the Reagan character

has reverted to being a boy; and the ending becomes

less morally apocalyptic. Naturally de Souca felt the

need to cinematise events, upping the ante visually,

and this brings in some Exorcist-esque

effects, but Possessed remains nicely

low-key in its use of horror clichés and the

result is a surprisingly good, and effectively dramatic,

film. Though low budget, it manages to generate decent

suspense and to work some good shocks, with the possessed

boy mouthing hair-raising language that I imagine was

expurgated for network showing. Timothy Dalton is the

film's biggest asset, however. His performance as the

tormented and despairing priest totally transcends the

cliché and carries us over the budget-driven

low-points, supported by a script that is generally

well-constructed and has its own integrity. I particularly

enjoyed the priest's scorn, directed toward the spitting,

hissing, spinning demon at the climax, where he says

derisively: "This is evil?"

18

October 2005

Return

to top

|

|

Dead

Birds (US, 2004) -- dir. Alex Turner

With

a good cast, an imaginatively appealing historical setting,

a terrific haunted mansion (complete with eerie surrounding

cornfield), an intriguingly Lovecraftian central idea,

and the availability of sets hired cheaply in the wake

of Tim Burton's Big Fish, this Civil

War demonic ghost story has a lot going for it, especially

in the light of its meagre budget. Director Turner shows

himself to have promise and Dead Birds,

his first feature, comes over as a visually interesting,

occasionally scary -- though inconsistent and under-developed

-- horror film.

Visually

Dead Birds works a treat, with individual scenes

that are extremely well handled. Yet I found it all

a little too familiar, even the "revolutionary"

use of its Civil War setting (which was there to provide

texture rather than substance). The film kept reminding

me of other films. Even the excellent "scarecrow"

moment, where a displaced comrade is found to be stuffed

with straw, resonates from a better film, Scarecrows,

about a bunch of robbers who, coincidentally, hold up

in an old house surrounded by haunted cornfields and

scarecrows -- and gradually get picked off by the vengeful

demonic inhabitants.

The

real problem, however, came from the character arcing.

The opening bank robbery (our introduction to people

we are about to spend 90 minutes with) is ill-considered

and gratuitous. We are supposed to care about their

fate as the film unfolds, but they are a bunch of unsympathetic

bastards from the start -- even Nicki Aycox's nurse,

who violently slaughters a bank teller for no purpose

other than to provide opportunity for a passing gag.

Subsequent attempts to induce empathy are tainted by

this macho beginning, which sets the tone of our emotional

responses, and is way more violent, emotionless and

bloody than the rest of the film put together. The "hero"

agonising over accidentally killing a kid doesn't carry

much conviction either, given he'd just shot some poor

old bugger (and others) in the bank for no very good

reason. From that point on, I just didn't care what

happened to the gang. If the robbery had simply "gone

wrong", resulting in deaths caused by panic, the

scene would have worked fine ... and would still have

had sufficient moral ambiguity to carry the rest of

the plot. But the writer and director were apparently

going for "hard-edged violence" and confrontation

rather than narrative/character effectiveness. The result

was a weakening of the overall effect.

That

said, Dead Birds offers lots of atmospheric

brooding and a good central idea, even if it isn't developed

with any great imagination. There are many quietly suspenseful

scenes (though few creepy moments). In a film this slow

moving, there needs to be enough imaginative input to

carry us through, and the slow pace should add to our

unease rather than diffuse it. Moments of ghostly visitation

provide quite a jolt, however -- and the "flashback"/nightmare

vision in the third act is a near-masterpiece of well-selected

imagery and effective editing.

I

guess this sounds pretty much like I didn't care for

the film at all. I did, in fact, up to a point; I simply

thought it could/should have been much better. I was

left with the impression (confirmed by the "making

of..." docu on the DVD) that the writer (Simon

Barrett) was not quite on top of things and allowed

himself to be bullied by a director with great potential

but who in this case didn't really know what story he

really wanted to tell.

3

October 2005

Return

to top

|

|

Premonition

[aka Yogen] (Japan, 2004) -- dir. Norio Tsuruta

Made

as part of the J-Horror Theater series (no. 2), Yogen

is a wonderfully imaginative and powerful film, with

moving central performances by its two principals, Hiroshi

Mikami (as Hideki Satomi, as college teacher) and Noriko

Sakai (as Satomi's wife Ayaka, a researcher at the same

college), and an original storyline only vaguely suggestive

of Ringu. Yogen is based on

the manga series Kyôfu shinbun

[or Newspaper of Terror] created by Jirô

Tsunoda. Its central image is of a dark and crowded

page of newsprint, which flaps out of the sky or otherwise

makes an appearance, in order to reveal a news item

concerned with violent death to come. What this knowledge

does to the characters to whom the premonition is given

is the central driving force of the story.

With

several shocking moments -- all superbly executed --

and many disturbing images, Yogen weaves

an intriguing and profound tale of personal destiny

and its interaction with the destiny of others. There's

not much that is predictable about this film and, unlike

the horror films we are more familiar with, it seems

as interested in involving your thought processes as

in scaring you. Conspicuously lacking in gorehound violence,

it uses deepening implication to disturb, along with

the odd visual frisson. In the end, it is the

characters that provide the narrative with its momentum,

rather than the unravelling imagery of the premise (as

good as the imagery is). The film's ending, to my mind,

is perfect.

23

August 2005

Return

to top

|

|

The

Uncanny (UK/Canada, 1977) -- dir. Denis Héroux

According

to the OED, the term "uncanny" means "untrustworthy

or inspiring uneasiness by reason of a supernatural

element; uncomfortably strange or unfamiliar; mysteriously

suggestive of evil or danger". It literally means

"unknowable", I believe. Given the suggestive

nature of that, any film with the word as its title

should be unsettling and creepy at the very least. Well,

this one isn't, even though it wants to be. It's a feline

horror anthology starring Peter Cushing, Ray Milland,

Donald Pleasance, Samantha Eggar and others and is second-rate,

if not absolutely terrible. Only really worth it for

Cushing's brief linking bits and Pleasance (who spoofs

himself and the film industry in his segment, as does

Eggar). The main problem is that the cats aren't filmed

with any degree of spookiness, apart from the occasional

cattish inscrutability. It's all too upfront. Héroux

couldn't even manage the old Cat-Leaps-Out-of-the-Cupboard

trick to get a scare. Most of the time the cats involved

look confused, slightly nervous or indifferent, rather

than vicious and manipulative, appearing to want to

be elsewhere. A bit like the actors, especially Milland

who comes over as bored and impatient. One day someone

will do a good cat horror film, extending the eeriness

created by the cat in Ju-On:

the Curse to the length of a feature.

I

did like the opening credit sequence, though, with all

its paintings of cats.

23

August 2005

Return

to top

|

|

Dracula

3000 (Germany/South Africa, 2004) -- dir. Darrell

Roodt

How

could they possibly go wrong? The most ancient and famous

of vampires turns up on a derelict spaceship being salvaged

by a typical bunch of misfits -- and then goes into

predatory mode. Very Alien, sure, but it should

be at least entertaining. The DVD cover looks very cool

-- a complex Giger-esque vampire, teeth bared.

Well,

they did go wrong. Very wrong. The film is

abysmal. It has some decent low-budget production values,

but the script, acting and direction are shockingly

bad. Okay, some of the actors make a brave attempt (and

their names will be withheld in consideration of possible

future careers). But most of their characters are awful,

often annoying. Nothing much happens that couldn't have

been written by an indifferent monkey with something

else on its mind. And the ending...

I'm

sure the production meeting that discussed it went something

like this:

Director

to writer (sounding somewhere between bored

and desperate): How are we going to end this thing?

Writer: Beats me. Does anyone care

by this stage?

Director: Oh, come on, we HAVE to have

an ending.

Writer: OK, but first we need some

sex between the Crew Member Who's Blonde and Wears An

Impractical Low-cut Tanktop, and the Totally Obnoxious

Testosterone-Driven Bully.

Director: That wouldn't make sense,

would it? She hates him.

Writer: Does it have to make sense?

Look, she's an ex sex-bot who's acting as an undercover

drug agent. That's the Big Revelation, right? Clever.

Director: It's a rip-off of "Alien".

Writer: It's a homage. But it was clever

then and it's still clever now. Besides, the robot in

"Alien" wasn't a sex-bot. Sex-bots are even

cleverer.

Director: OK, OK. Whatever.

Writer: So if she's an ex sex-bot,

she'll have sex with anyone, even a Stupid Mindless

Hunk That She Hates. Women are like that. Especially

if they're sex-bots.

Director: But we can't have a sex scene.

Erika only agreed to do the role if it didn't include

her being naked.

Writer:

But she's been in Playboy. I thought that's

why we got her.

Director: She wanted to Get Serious.

Writer: Really? Okay, never mind. I've

got it covered. They don't actually get to have sex!

Leaves the audience with a lot of Unfulfilled Sexual

Tension, see? Very popular.

Director: Still doesn't give us an

ending.

Writer: Well, while the audience is

distracted by the possibility that something interesting

might be going to happen -- after all, they've wanted

to see Erika nude the whole way through the picture

-- we'll blow up the ship.

Director: What? Why? We haven't set

that up. It doesn't make sense.

Writer: Sure it does. We've got Udo

Kier on contract. He'd blow up a ship. Everyone

knows that.

Director: But even if he would, why

just at that moment?

Writer: Because we want to end the

picture. Why else?

Director: That's terrible.

Writer: Hey, it's an ending, You can't

deny that. And a tough one. Everyone dies. Very arthouse.

Director: No audience'll buy it.

Writer: Sure they will. They couldn't

give a rat's arse about any of the characters anyway.

In fact, they hate them all and by this time just want

the damn movie to end.

Director: We might as well have a Space

Volcano that erupts suddenly and kills everyone.

Writer: Hmmm, not bad. Sort of cross-genre

homage to ... something I've forgotten. Very postmodern.

Let's do it.

Director: Forget it. We've only got

twenty bucks left. Can't afford to build a volcano.

We'll stick with blowing up the ship. The SFX department'll

like that. He hates that ship.

Writer: Cool. I'll write it into the

script.

Director: I didn't know there was

a script. Who took my copy?

I

sold the DVD immediately after watching it.

17

August 2005

Return

to top

|

|

Zombie

Honeymoon (US, 2004) – dir. David Gebroe

Though

its title suggests something comedic, if not farcical,

Zombie Honeymoon is in fact an often

moving meditation on the dilemma of finding that the

one you love has become something increasingly hard

to relate to. Denise and Danny have just married and

are deliriously happy and deliriously in love. While

honeymooning, Danny is assaulted (rather grossly) by

a zombie that lurches out of the sea. Danny dies, but

ten minutes later is back, apparently normal. But all

is not as it seems. Not only did Danny die, he

is still dead – has become one of the cannibalistic

living dead, in fact – and proceeds to chow down

on random visitors to their house, compulsively and,

afterwards, with genuine regret. What is Denise to do?

She loves him, but he keeps eating their friends.

While

the film has its grimly humorous moments, the narrative

isn’t handled as farce. Denise’s emotional

dilemma is treated seriously and the carefully modulated

performance of Tracey Coogan successfully carries a

heavy emotional load. The cannibalistic scenes are gross

and bloody, in the tradition of Romero’s living

dead movies, but the end result is a sort of black-tinged

pathos that is both profound and metaphorically resonant.

As he becomes more and more zombie-like, visibly rotting

and swapping the power of speech for a pained wheezing

groan, we can’t help but sympathise with Denise’s

desperate confusion. The image of her sitting in their

bedroom watching a cooking show on TV, turning up the

volume to muffle the hideous sound of Danny eating a

policeman, is wrenching, outrageous, and infinitely

sad.

The

director deserves recognition for his great achievement.

Managing to bring together traditional Romeroesque zombie

tropes with those of a tragic romantic drama is not

something to be taken lightly.

29

July 2005

Return

to top

|

|

They

Came Back [aka Les Revenants] (France,

2004) – dir. Robin Campillo

A

re-envisaging of the zombie film that incorporates Haitian

zombie ambiance into the dominant Romero scenario, Les

Revenants is very nearly a classic, in the

end suffering somewhat from its own determined emotional

distance and the lack of narrative conviction in its

ending.

Beginning

with a superbly unsettling scene of hundreds of the

dead returning to life en masse through the gates of

a cemetery, Les Revenants seeks to

explore attitudes to death and loss through a narrative

involving the reintegration of the dead back into society.

These zombies are not decayed, flesh-eating monsters;

they are whole, undamaged, clean and filled with zen-like

calm. They can talk and to all intents and purposes

appear to be as they were before death took them –

better perhaps, as whatever disease or accident was

responsible for their death has left no scars. Slowly

they remember their past; yet slowly, too, they appear

to their families and friends as more and more distant

and alienated. Finally it is clear that all they have

is memory; they have no initiative, no awareness of

the future. They are removed from ordinary life, like

faded photographs (a conceit reinforced through the

use of flat lighting and predominantly white clothing).

Dead, they existed only in the past. Returned from death,

they exist in the present but remember the past. But

being alive means existing in the past, present and

future. Therefore, however they might appear, they are

not alive. In fact they are like corporeal ghosts, physical

phantoms haunting the living. As a metaphor for failing

to let go, the concept works beautifully and the exploration

of it, particularly in the relationship between a young

woman (Géraldine Pailhas, in an excellent and

finely nuanced performance) and her dead husband (Jonathan

Zaccaï), is movingly handled.

Many

moments within the film are quietly chilling and unsettling,

redolent with an incongruous but numinous terror, and

the emotions displayed are wonderfully complex, as families

find that their own responses to the return of loved

ones are not as unambiguous as they might have hoped.

But

Campillo seems to be so intent on maintaining a non-exploitative

horror tone throughout that he trips up the narrative

and makes the film’s progress as flat and “removed”

as the zombies themselves. His one attempt at “action”

is ill-conceived and pointless, as he tries to push

the film toward some sort of climax. The zombies’

acts of sabotage seem unnecessary, both within the plot

and thematically; if the sabotage was intended as a

distraction to allow the dead to “escape”,

the real effect is just the opposite. And the reaction

of the authorities, though suggestive of the end of

Romero’s Night of the Living Dead,

begs way too many questions as regards the director’s

avowed attempt to keep the film within the bounds of

the real; is it conceivable that the authorities could

destroy the dead like this, on such a flimsy pretext,

without provoking massive protest and even civil action?

I don’t think so. It wouldn’t matter except

that these things – the sabotage and the attack

on the dead – seem so out of place that we are

forced to question them. Throughout the film Campillo

and his characters resolutely fail to ask the obvious

questions or express a natural curiosity as to how the

dead can return and what the experience of death was

like for them. I neither want nor expect an answer to

these questions and the lack of questioning can be accepted

within the context of a parable. But the sabotage and

its consequence demand explanation, and when we don’t

get it, or even a hint of what it might be for, it causes

us to start questioning more widely.

For

me a more effective ending, and one that arises more

naturally from the first two acts, would have been for

the zombies to simply disappear, gradually and without

fuss fading into shadows, as both they and their loved

ones realise that the dead simply don’t belong,

and can never be re-integrated into their old lives.

This makes sense thematically (and metaphorically),

whereas Campillo’s existing ending remains unsatisfying

and incongruous.

It’s

a pity. There is great beauty and a profound pathos

in this film, undercut at the end by confused methodologies.

29

July 2005

Return

to top

|

|

Shock

Waves (US, 1977) -- dir. Ken Weiderhorn

As

aquatic Nazi zombie movies go, Shock Waves

is a classic. Made by Ken Wiederhorn, otherwise renown

in the genre for the not-very-memorable Return

of the Living Dead II, it is an enjoyable low-budget

zombie flick that has become something of a cult favourite

over the years, and provokes its fair share of chills.

Set near and in the midst of a semi-tropical island

marshland (complete with decaying colonial mansion),

it is atmospheric and often suspenseful -- and only

falls down in being somewhat narratively underdeveloped.

Visually, despite its rather dark and indistinct appearance,

it is a delight. Even the film's dirty graininess can

be extraordinarily effective, as in the rise of the

ghost ship, which, no longer on the ocean floor, bears

down on the protagonists' boat during a weird and unsettling

storm at sea.

The

cast includes veterans Peter Cushing (looking typically

gaunt and authoritative as an ex-Nazi commander), John

Carradine (looking typically gaunt and haggard as a

hire-boat captain), Brooke Adams and Luke Halpin. They

all do a good-to-servicable job. Even better are the

Nazi zombies, members of an elite "not-quite dead

and not-quite alive" SS death corps, whose transport

was scuttled (by their non-undead commander) at the

end of the War when their existence had become problematic,

and who have now returned to do what ex-mass murderers

and psychopaths do when they've been resurrected as

zombies: kill without rhyme or reason. Memorable scenes

of SS zombies lying just beneath the surface of ponds

and rivulets or prowling the off-shore ocean beds in

jackboots, black goggles and decaying skin are alone

worth the price of admission. As befits their elite

corps status, these zombies stalk confidently through

the mangroves and kick in doors with aplomb -- though

they're also not averse to standing half visible in

the mangrove shadows and simply watching. Such

moments linger in the mind.

The

film does feel under-written, however -- not in terms

of existing dialogue, but as regards narrative content.

Cushing's character, superbly realised by the horror

maestro, is underused. In fact, I would have liked the

story to concentrate more on Cushing's aging SS commander,

who has exiled himself here on the periphery of the

Death Corps graveyard in nostalgic guilt or fear, rather

than on the doomed victims who have wandered into this

piece of resurrected history and are now forced to relinquish

their tenuous hold on life. Unfortunately the commander's

fate remains somehat off-hand -- though the film ends

with a melancholy and chilling fatalism that is both

redolent of the period and strangely haunting.

15

July 2005

Return

to top

|

|

House

of the Dead (Canada/US/Germany, 2003) -- dir.

Uwe Boll [aka House of the Dead: Le jeu ne fait que

commencer]

The

tagline of this zombie light-weight reads: "The

dead walk... you run". Not quite accurate. Though

this post-Millennial zombie flick references Romero's

Living Dead classics as an inspiration, the zombies

actually run, leap and utilise assorted weaponry in

a way totally alien to the Romero dead. The real inspiration

behind the film, in fact, is the Sega game of the same

name, and the House of the Dead references the

game constantly, not simply on a Sega banner decorating

the stage at "the rave party of the century"

but by continually inter-cutting the game's actual graphics

into the action. This -- and the unending, ultra-stylised,

Matrix-esque fighting -- are the two single most annoying

things about it. Together they manage to effectively

undermine whatever audience involvement the film might

have achieved.

This

is a pity. True, the situation and basic plotting are

totally unoriginal. Indeed when I read the synopsis

-- horny young groovers go to weird island for a rave

and end up being chased and killed by zombies -- I was

tempted not to bother. Though there is slightly more

to the plot (a bit of interesting back-story), the "more"

is so token it doesn't make much difference to the overall

effect. Vacuous characters get killed by zombies. That's

it. Admittedly there is a hell of a lot of running around.

And stylised fighting. Did I mention the stylised fighting?

A lot of it is in slo-mo, utilising a tedious 360-degree

sweeping motion centred around whatever character is

being thus heroically re-envisaged -- a technique that

was stolen from umpteen more effective Japanese and

Hong Kong martial arts films, not to mention The

Matrix. (Come to think of it, the Japanese

zombie/yakuza epic Versus had to be a stylistic

inspiration for this film; it stole from The

Matrix, too, but rather more creatively.) But

how is it that a bunch of boneheaded twenty-somethings,

who can barely remember their own names and spend a

lot of their time drinking and fumbling at various items

of clothing, suddenly prove to be superhuman kickboxers,

kung fu fighters and experts in both modern and ancient

weaponry? That was the real mystery, not where the zombies

came from.

The

"pity" aspect mentioned above arises from

the fact that the actual cinematography looks clear

and professional (though not the directorial decisions

relating to it), the setting is wonderfully picturesque,

one or two of the actors are OK (Jurgen Prochnow in

a stereotypical role and Ona Grauer, whose character

at least appears to have a few brain cells), the design

work is good and the zombie make-up occasionally effective.

Then they go and spoil it by being too damn hip and

thoughtless for their own good.

The

only sign that this is a post-Millennial zombie film

is the metal/techno/hip-hop soundtrack and the slo-mo

bullet POV stuff. In storyline it's bad Romero ... no,

it's post-bad Romero, being more like one of those 1980s

Italian Romero rip-off flicks, like Zombie

Holocaust: sexploitation, bloody zombie action,

experiments in longevity by mad scientist (or in this

case long-dead de-frocked medieval priest). In short,

nothing new, technically competent with good-looking

cinematography and design work, terrible directorial

decision-making, dumb flat-line story, a script full

of bad dialogue and logic flaws, and lots of gory zombie

action.

30

June 2005

Return

to top

|

|

13

Ghosts (US, 1960) -- dir. William Castle

While

watching this "gimmick" horror film from legendary

cinema showman William Castle, it occurred to me that

13 Ghosts needs to be considered as

working in a different genre to other horror films.

There's little point in watching it as an ordinary horror

film, that is, as an artistic experience wherein disbelief

is suspended and the appropriate emotions are provoked

in you by the immediacy of the on-screen drama and the

power of its atmospherics. Instead, 13 Ghosts

stresses its own artificiality, glorying in its status

as a piece of celluloid gimmickry and forever reminding

you that it's all a thrill ride. Most horror films have

an element of the "thrill ride" mentality

about them, but Castle makes it his film's reson

d'être. The experience of being in the theatre

and screaming your head off with your mates while playing

hide-and-seek with the "ghosts" is what it's

all about.

Famously,

13 Ghosts was shot in Illusion-O, a

dubious technique invented by Castle that allows an

audience to see or not see the onscreen ghosts as they

wish. A cardboard viewer with separate blue- and red-tinted

lenses was supplied at the door. Are you brave? Then

look through the red part of the viewer to see the ghosts,

Castle explains. If not, look through the blue part

and the ghosts will disappear. Of course, you can see

the ghosts even without the viewer, but nevertheless

the illusion of having an option was a clever marketing

stratagem and, no doubt, involving for the original

audience of spook-show enthusiasts. The trouble is,

though the film is mostly in black-and-white, the screen

is tinted whenever the ghosts are about to do their

thing and a sign appears at the bottom saying "USE

VIEWER". When the ghosts have gone you are admonished

to stop using the viewer. As a result of all this signposting,

there's little tension, no unanticipated scares and

a continual reminder that the whole thing is a fake.

Castle's beginning monologue, with its corny if endearing

visual gags, simply adds to the feeling of artificiality.

Of

course, you could always watch the TV version that is

purely in black-and-white, without Castle or the tinting,

but where's the fun in that? The idea behind the film's

scenario might have had potential -- the past owner

of the house having collected ghosts and our brave all-American

family, having inherited the place, now need to deal

with them, using special glasses that make the spooks

visible. But Castle doesn't develop the concept much

at all (just as he never develops the idea of the mysterious

13th ghost), and both the staging of the ghost scenes

and the weak climax are too theatrical to generate anything

by way of chills -- unless you're willing to play Castle's

"peek-a-boo" game and consciously pretend.

The

current DVD re-issue offers a nice clear print (of both

versions). Though the glasses are said to be supplied

and aren't, you can always make your own in order to

play along with the gimmickry of it all. Might be fun

in a group.

Just

don't expect to be engaged by the drama itself.

27

June 2005

Return

to top

|

|

The

Story of Ricky (HK, 1991) aka Riki-Oh,

Lai wong (original title), King of Strength

(literal translation of HK title) -- dir. Ngai Kai Lam

1980s

Italian zombie movies (see Burial

Ground and Fulci's Zombie Flesh

Eaters). Raimi's Evil Dead.

Jackson's Bad Taste and Brain

Dead (Dead Alive in the US).

Gordon's Re-Animator, From

Beyond and (interestingly) Fortress.

Still with me? Add a big helping of Shaw Brothers kung

fu martial arts. Also the Sonny Chiba bone-cruncher,

The Streetfighter. Mix well.

If

the above stew settles nicely in your stomach rather

than compelling you to reach for a bucket, then you

might be interested in Lai wong (Story

of Ricky). Just out on Region 4 Hong Kong Legends

DVD (uncut Collector's Edition), it actually lives up

to its cover blurb (except for the bit about The

Matrix... no relation there, folks), offering a

non-stop pageant of head-splitting, gut-slicing, blood-splattering,

eye-gouging, limb-removing and body-mincing -- all in

the name of good clean down-and-dirty action entertainment.

Based

on a rather violent Japanese manga, Lai wong

places its supernaturally strong hero, Riki-Oh, in an

alternative-reality, futuristic (2001), corporatised

prison, where he must slice heads apart with his bare

hands just to survive (and to stand up for The Right).

As has been proven in the past, it's a good scenario

for a film of this kind -- claustrophobic and otherworldly,

open to psychopathic behaviour, rampant self-interest

and aggressive violence. Once it's established that

the hero is ethically driven and a decent bloke, then

the audience can readily give in to his sense of battered

injustice and its manifestation in the form of gorily

comicbook fights.

Of

particular interest is the way that fantasy elements

are introduced without the need for rationalisation

or undue embarrassment. This film takes the implicit

unreality of action films and ramps it up several notches.

Riki is super-strong and has been from birth. Yeah,

OK. He's an Asian Hercules. He can pound his fist

through a gut or a prison wall or steel bars with a

single blow. Cool, eh? He can have the muscles

of his arm sliced open and heal the injury, mid-fight,

by tying the tendons back together with his other hand

and his teeth. Can't everyone? Razorblades

through the cheek. Spike through palm. Spear through

leg. Lay it all on him and he can still fight. Of

course he can. A big bugger of an opponent can

reach into his own abdomen, haul out his intestines

and use them to strangle Riki. He's certainly got

guts, as the spectators remark. Elephant gun cartridges

can be shot into someone and cause them to blow up like

a balloon before exploding. Sure, happens all the

time around here. The warden suddenly turns into

a huge ogrous monster for the final conflict, in order

to put the rebellious Riki in his place. What? Really?

OK, I can live with that -- aren't all action film bad-guys

monsters at heart? One thing's for sure -- anyone

who rents this film expecting a Jackie Chan clone are

in for one hell of a surprise!

For

sheer in-your-face violence and fantastical gore, you

have to give director Ngai Kai Lam his due. But while

it's undoubtedly bloody and a little confronting for

your granny, it's not overly realistic and is so extreme

as to veer into parody, much the way Brain Dead

and Evil Dead did. So is it a horror

comedy like those films? Well, yes, though its overt

origins in the martial arts/action film tradition give

it a pseudo reality that those films never courted --

and hey [said in an ironic tone] who could deny the

reality of action films? (Note: Riki actor Siu-Wong

Fan does his own stunts and is adept at most martial

arts, or so he says in the rather interesting interview

included on the DVD. So that aspect is real!)

Basically,

Lai wong does what it set out to do,

and does it with gusto -- despite the rather rubbery

look of most of the body-dismemberment SFX. For a viewer,

liking it or not liking it will definitely come down

to a matter of taste. But be sure to watch the subtitled

version. You wouldn't want the irrelevant unreality

of the dubbing to distract you from the much more relevant

unreality of the gore and violence itself.

Another

note: This was apparently the first HK film to

receive a R-rating for violence rather than sex.

25

May 2005

Return

to top

|

|

The

Invisible Ghost (US, 1941) -- dir. Joseph H.

Lewis

There's

no literal ghost in this film, invisible or otherwise.

But there is a phantom haunting Charles Kessler (Bela

Lugosi). Though provoked by an imagined ghost (that

of his missing and amnesiac wife, returning now as a

rain-drenched face at his window or benighted spectre

on his lawn), the real ghost remains invisible to everyone

else; it is the unresolved emotion that manifests in

Kessler as a mindless, homicidal rage.

This

film -- the first of Lugosi's el cheapo horror

flicks for Monogram in the 1940s -- offers up a badly

worked-out scenario, but it is atmospheric

and provides strangely fascinating entertainment on

a B-grade level. Lugosi plays his part with considerable

dignity and is effective in a sinister (when homicidal)

but sympathetic role. The tragedy is his, despite the

corpses of strangled victims that litter his house.

Good light-and-shade photography, decent acting and

imaginative direction create many memorable images,

giving the impression that it was only lack of a decent

budget that prevented the narrative from being developed

in a way more dramatically feasible than was managed

in the available space. If the story could have expanded

beyond the house, many of the logical absurdities and

shallow melodramatics of the plot would have been minimised.

But

despite everything the film does work as a sort of metaphor

-- an absurdist poem that plays liberties with naturalistic

expectation. The version I watched on Flashback DVD

was sepia in tone rather than clear black-and-white.

Whether this reflects the original or not, this quality

actually served to give the tale the resonance of a

recollected nightmare.

23

May 2005

Return

to top

|

|

Exorcist:

The Beginning (US, 2004) -- dir. Renny Harlin

Over-reaction

is a tradition among fans and critics. I came to Harlin's

much-maligned prequel to the 1973 classic with very

low expectations. His career has not been all that stunning

(though to be frank I don't think it's been all that

bad either: Die Hard 2 (1990) was a

pretty good action movie -- as was the generally under-rated

The Long Kiss Goodbye (1996); I've

always enjoyed Prison (1988) for what

it was -- and what it was was a gaudy comicbook horror

flick, just like his Nightmare on Elm Street

4: The Dream Master (1988), which wasn't the

best of the series but worked on the level of B-grade

visual posturing; and his other recent horror/action

blockbuster, Deep Blue Sea (1999),

had its moments -- though it gave me a headache, I recall,

and that didn't put me in a particularly receptive critical

mood. None of these were great films by any stretch

of the imagination, but they were above-average exploitation

movies, which is what Hollywood seems to go for post-Jaws).

Harlin's strength has been in action and the exploitation

of genre tropes. So when he inherited The Exorcist

prequel from Paul Schrader, under circumstances guaranteed

to set everyone against him, it looked a little like

we were in for a typical non-horror action-film riff

on the horror classic. This seemed particularly likely

when it was revealed that Schrader's version was felt

by studio execs to lack the right clichés [not

their words] to satisfy the "target audience"

(of 14-year-old boys, presumably).

And

the initial response was predictable: critical scorn,

fannish loathing, rampant dismissiveness.

Expecting

it to be awful, I waited to see the film on DVD rather

than at a cinema and long after bucket-loads of abuse

had been directed at it. Well, in the event I didn't

find it to be awful, despite the scorn. Nor was it simply

an action film -- nor a teen body-count slasher re-cast,

for that matter. Of course, it also wasn't original

or subtly horrific. But it wasn't dreadful. Like Prison

and Nightmare on Elm Street 4: The Dream Master,

it was a fairly typical B-grade exploitation film, only

this time for the 2000s -- that is, expensive and with

high production values and plenty of CGI, yet still

essentially exploitative. That's OK. I enjoyed it for

all that. It had some excellent visual design and offered

darker, claustrophobic aspects to balance the box-office

appeal of occasionally unnecessary blockbuster spectacle.

The actors worked hard at giving their characterisations

depth. The archeological aspect was imaginatively exploited,

too, and made the film feel less typical. (Maybe that

was a problem; like Exorcist 2, opening

the scenario out to include more exotic locales created

an ambiance significantly different to the suburban

mundanity of the original Exorcist's

setting -- a difference that did not allow its extreme

demonic imagery to gain power by playing out against

a contrasting and familiar background.) At any rate,

the film's narrative developed efficiently and played

out with enough drama to keep me interested, even though

it wasn't exactly my ideal of an Exorcist

prequel.

From

what I've read (and from my opinions regarding the displaced

director), Schrader's version might be more powerful,

less stereotypical, and more character-focused. Will

it be more horrific? Not according to the studio execs

-- though that may reflect their definition of "horror"

rather than its actual emotional impact. Who knows?

Perhaps his film will seem more like a worthy extension

of the original. It's rather unique that we'll get a

chance to decide for ourselves.

But

whatever Schader has produced, Harlin's effort, taken

separately, felt like a enjoyable exploitation horror

flick, with high-ish production values, effective if

rushed characterisation, and some muted thematic impact.

To totally reject it on the basis of what it isn't would

be, in my opinion, an over-reaction.

11

May 2005

Return

to top

|

|

The

Changeling (US, 1980) -- dir. Peter Medak

Clearly

conceived as a high-quality supernatural thriller --

with a prestigious cast that includes George C. Scott

and Melvyn Douglas and a director whose background is

in stage adaptations -- The Changeling

comes over as an effective haunted house film, with

an intriguing mystery gradually unravelled by Scott's

grief-damaged composer and enough chilling moments to

satisfy the viewer's expectations of numinous terror.

It is, however, dramatic rather than genre exploitative,

and for me at least more often provoked feelings of

sorrow than of terror.

Particularly

effective, however, is the role of sound in creating

its most chilling moments, especially appropriate given

the fact that Scott's protagonist is a composer seeking

relief from his own tragedies and a renewal of inspiration

in the Seattle mansion that stands at the centre of

events. Thumpings, peripheral noises, even the small

sound of a bouncing ball are used to great effect. The

set, too, is impressive, built, I believe, at great

expense and dealt with rather decisively at the end.

Its stairways and passages take on a sinister character

of their own that allows us to feel something of the

characters' growing dread.

But

the film works, too, as many ghost stories do, in terms

of a mystery to be solved, as the past -- forced into

frightful action by resentment, loneliness and a great

sense of injustice -- struggles to find resolution through

the main character's vulnerability.

2

May 2005

Return

to top

|

|

13

Gantry Row (Aust, 1998) -- dir. Catherine Millar

Decent

acting and effective dialogue, a carefully measured

pace, and a setting that (for Australians anyway) gives

the film a certain familiarly picturesque interest serve

to obscure the somewhat unoriginal nature of this haunted

house drama. Rebecca Gibney and John Adam play Julie

and Peter, a yuppie couple who buy an old house in an

exclusive street (in the Harbour-front Rocks area of

Sydney), with the intention of renovating it into a

liveable state, even though it means putting themselves

seriously into debt. As they struggle to make the house

over, sinister forces from the past arise to thwart

their attempts at re-creation. It is, above all things,

an upper middle-class nightmare.

As

Stephen King has pointed out in regards to The

Amityville Horror (in Danse Macabre,

his book on horror fiction and its meanings), much power

can be gained by appealing to an audience's fear of

financial vulnerability and ruin. Ghosts are implicitly

about death, but in horror fiction fear of death is

often part of a much wider concern -- fear of change

and loss of control over ordinary life and the expectations

we have of it. In 13 Gantry Row, these

fears are admirably captured with an occasionally unnerving

intensity.

To

the film's credit, the emphasis remains on the couple,

their new/old house itself becoming a metaphor for the

tensions that can simmer beneath the surface of even

the most apparently stable relationship, sparked into

life by hidden currents in the world and in themselves.

The rising tensions are effectively imaged as a watery

stain that crawls upwards on the wall, becoming more